|

| Venezuela's Hugo Chavez |

On March 2006, Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez announced that he would have no problem expropriating real estate properties from owners who refuse to sell at regulated prices.

"If someone in Caracas has five apartments and refuses to sell at the regulated price, we'll implement an expropriation decree for the public good and pay the owner what the apartment is really worth!" said Chavez, who was first elected in 1998.

Invasions of property by poor people have occurred throughout Venezuela, with the government turning a blind eye. The administration openly tolerates the violation of property rights. In Altos Mirandinos, 683 'property invasions' were recorded in 2005 in which houses were simply seized by squatters. Property-owners in some towns have even formed self-defense forces to avert building invasions.

The lack of new supply caused by Chavez' policies has made Venezuelan real estate actually rise in price by 35%, according to the President of Metropolitan Real Estate Chamber of Commerce, though the claim is largely rhetorical, because the uncertain situation is not good for property values.

|

| (L-R) Argentina's Kirchner, Bolivia's Morales, Brazil's da Silva, and Venezuela's Chavez |

Chavez won a third term as president this December, with 60% of the popular vote. The middle class seems in for a rough ride. The irony is that Chavez is addressing a housing crisis he himself partly created. His government has built an average of 16,000 new houses a year. This is much less than his predecessors' 65,000 a year.

"Today a new era has started, with the expansion of the revolution," Chavez told the celebrating crowd in his re-election victory. He announced that during the next 14 years, he would transform Venezuela from a capitalist to a socialist society.

With the re-emergence of the left in Latin America, how much risk is there for private property owners and investors in residential real estate?

The red and the pink

The fear of another Chavez-type leader is well based. Latin America appears to be going through a continent-wide reaction to the perceived failures of the previous decade's experiment with liberalization and free markets.

Yet there are of course degrees of socialism. Chavez is on the socialist left. Bolivia's Evo Morales (elected President December 2005) and Ecuador's Rafael Correa (November 2006) are certainly socialists, but arguably more pragmatic. Other leftist presidents include Argentina's Nestor Kirchner (May 2003) and Nicaragua's Daniel Ortega (November 2006), who are high-spending populists rather than fundamentalist leftists.

|

| Ecuador's Rafael Correa |

Ecuador's Rafael Correa, an avowed admirer of Chavez and Morales, however, won a run-off election only after moving closer to the center and toning down on anti-American tirades.

"It is necessary to overcome all the fallacies of neoliberalism," Correa has declared. However after the elections, Correa assured voters that he would not modify the "dollarisation" of the economy, despite the fact that he opposed the September 2000 scrapping of the local currency, the sucre, and adoption of the US dollar. The centerpiece of his plan is a fairer split of revenues with the oil companies, and a reduction of environmental damage. Yet he has declared himself against oil nationalization.

Correa, who studied economics in the United States and Belgium, describes himself as a "Catholic humanist." He has expressed sympathy for Latin America's left-leaning governments of Argentina, Bolivia, Venezuela, Brazil, Chile and Uruguay.

The list is indicative of his political views - to the left of moderate leftists like Luiz In'cio 'Lula' da Silva of Brazil (October 2002 and reelected in 2006), but definitely to the right of Chavez, who he considers a personal friend.

Correa is however not going to find it easy to implement his socialist proposals, not least because he has little support in Congress. Battles between the presidency and the legislature are commonplace in Ecuador, and these tensions will persist. Many doubt he will last the full four years of his presidential term, since no one in the past decade ever did.

|

| Bolivia's Evo Morales |

Bolivia's first indigenous President Evo Morales, another friend and admirer of Chavez, announced the re-nationalization of the oil and gas industry on May 2006. However this does not involve the expropriation of foreign companies, simply an (agreed) transfer from shared-risk contracts to operating contracts.

Morales has successfully pushed through congress, as Chavez did, a law that will allow him to redistribute up to 20 million hectares of 'idle' agricultural land. However there is no mention of seizing housing units from rich Bolivians.

Moderate centre-left

In the moderate social democratic court are Brazil's Lula, Peru's Alan Garcia (elected June 2006), Costa Rica's Oscar Arias (March 2006), Chile's Michelle Bachelet (January 2006), and Uruguay's Tabar' V'zquez (March 2005).

Uruguay's first centre-left president, Tabare Vazquez, is more concerned with social justice than undoing the benefits of economic liberalization. He has launched programs ranging from food assistance to healthcare.

|

| Chile's Michelle Bachelet |

Chile's first woman president, Michelle Bachelet, is also centre-left. She will continue the country's free-market policies, while increasing social benefits to reduce Chile's inequality, which is among the highest in the world.

In Peru, centre-left Alan Garcia defeated Ollanta Humala, a follower of Chavez. From the standpoint of the business community, it is very clear that the once-socialist Garcia was the lesser of two evils. Since taking office he has bent over backwards to show Peruvians and the outside world that he is not the same Garcia that messed up in the late 1980s.

Real estate markets up

Many of the Latin America's real estate markets are moving sharply up. Central America is experiencing a real estate boom, especially Costa Rica and Panama, but also swathes of Mexico, and is now a happy hunting ground for US second-home buyers.

|

| Nicaragua: A cheaper alternative to Costa Rica |

Even Nicaragua is trying to attract retirees and investors to the real estate market. It offers itself as a cheaper alternative to Costa Rica. 'The Costa Rican property market is completely saturated,' says Jaime Wheelock of the realtor Nicaragua is Hot.

"Nicaragua is only 45 miles from Costa Rica. The price difference is 1,000%. You can buy the same lot here for US$300,000 that you can buy a property in Costa Rica for US$3 million," says Wheelock.

According to Global Property Guide research, rental yields for houses and flats in Nicaragua's capital, Managua, range from 10 to 15%. The rental laws are pro-landlord and there are no restrictions on foreign ownership of residential real estate. To encourage foreign investments, the government passed Law 306 that gives investors 10-year exemptions from income and real estate taxes.

Outside the retiree belt in Latin America property, Argentina and Uruguay have seen strong price-recoveries.

|

| The Paris of Latin America |

In Argentina, Buenos Aires, dubbed the Paris of Latin America, offers beauty and charm at relatively low prices. While President Kirchner is on a spending spree, re-nationalizing and founding state enterprises ranging from water, postal and airlines, there are no indications that private real estate is on his buying list.

Uruguay property prices have also moved up very sharply. Strongly impacted by the economy of neighbouring Argentina, Uruguay attracts visitors because of its good security, excellent beaches, and 'first world' feel.

Uruguay does not suffer from serious peace and order issues or tumultuous regime changes. It is the first country in Latin America with an advanced welfare system. The Global Property Guide finds Uruguay's stability reflected in its high rental yields, at 7 to 12%, due to the large number of foreigners and tourists competing for limited rental supply.

Property rights in Uruguay are highly protected and there are no restrictions on foreign ownership. The laws applicable to the rental market protect the rights of landlords, and rental income tax and CGT are nonexistent. (In a recent survey, the Global Property Guide gave Uruguay a 5-star investment rating, our top rank).

The rest of Latin America has seen less price movement (even Argentina and Uruguay's price-rises are really recoveries). However there is little sign that the wave of elections of left-wing governments has had a seriously deleterious effect on property prices.

Slums and inequality

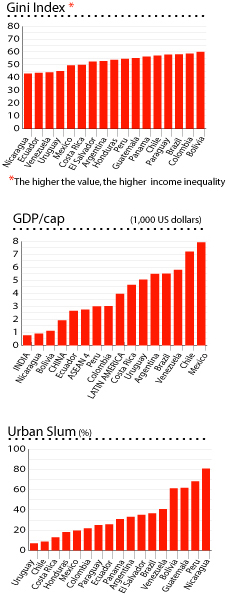

Why is Latin America vulnerable to periodic waves of populist leftism? The answer is simple: Inequality levels in Latin American countries are among the highest in the world, and its political cultures are structurally undemocratic. Political and economic elites dominate the system, the descendants of the colonizers.

Inequality in Latin America fuels social tensions and makes people susceptible to empty promises of dole-outs from populist candidates. The mestizo elite are associated with free-market capitalism and globalization, which thus becomes an ideological target of leftists and socialists in their rise to power.

The widening gap between the rich and the poor is especially pronounced in housing. Latin America's central business districts are typically surrounded by slum communities. The percentage of urban populations living in slums is very high, peaking at 81% in Nicaragua.

This means the region is in some ways different from other developing regions, such as for instance Southeast Asia. Poverty and inequality are much higher in Latin America (although Latin America's GDP per capita is also higher). Arguably this is an explosive mix. As income levels rise, economic inequality seems to become harder to bear. While urban slums exist throughout the globe, the level of crime and violence in Latin America is unparalleled.

Neither the political left nor the right has the answers. The present leftist reaction suggests that Latin America will continue to experience 'storm and stress'. The excluded will continue to demand inclusion. The elites will fight back against ideologies that they see as destructive and irrational.

Latin America appears to have not yet found a way out of this fundamental conundrum.